Souths Gonna Do It Again Sticker

The Due south's Gonna Do It (Again): Charlie Daniels, the Confederacy and the Rise of the New Due south in the '70s.

Charlie Daniels had his outset hit in 1973, just three years shy of his fortieth birthday. He had been kicking around for a while, playing dives and sessions — anything that would bring in a paycheck — but he outset attempted a solo career in 1971, afterwards he amassed just enough clout in Nashville to snag a contract with Capitol Records. This was the same yr the Allman Brothers Ring released At Fillmore E, the double-live LP that turned the Georgian group into superstars and had a profound impact upon Charlie Daniels, who up to that point had proven himself to be a deft weathervane following the shifting winds of American roots and stone music in the '60s.

After his career-defining 1979 boom "The Devil Went Downwards To Georgia," Daniels would be understood as a country music institution, even earning induction into the State Music Hall of Fame in 2016, merely the first 25 years of his career could hardly be chosen strictly country, although his music could always be classified as Southern. Fittingly, his Charlie Daniels Ring played a pivotal role in the ascent of Southern Rock in the 1970s, creating a rallying call for the movement with "The South's Gonna Exercise It" in 1975.

By tipping his hat to his peers with "The South's Gonna Do Information technology," saluting everybody from the Marshall Tucker Ring to ZZ Acme, Charlie Daniels acknowledged how a New S had emerged in the wake of the Civil Rights movement, i that seemed progressive every bit information technology embraced some hippie ideals. The music's rise in popularity ran parallel to the rise of Jimmy Carter, the idiosyncratic Democratic governor of Georgia who had a key ally in Phil Walden, the mastermind behind Macon, Georgia's Capricorn Records.

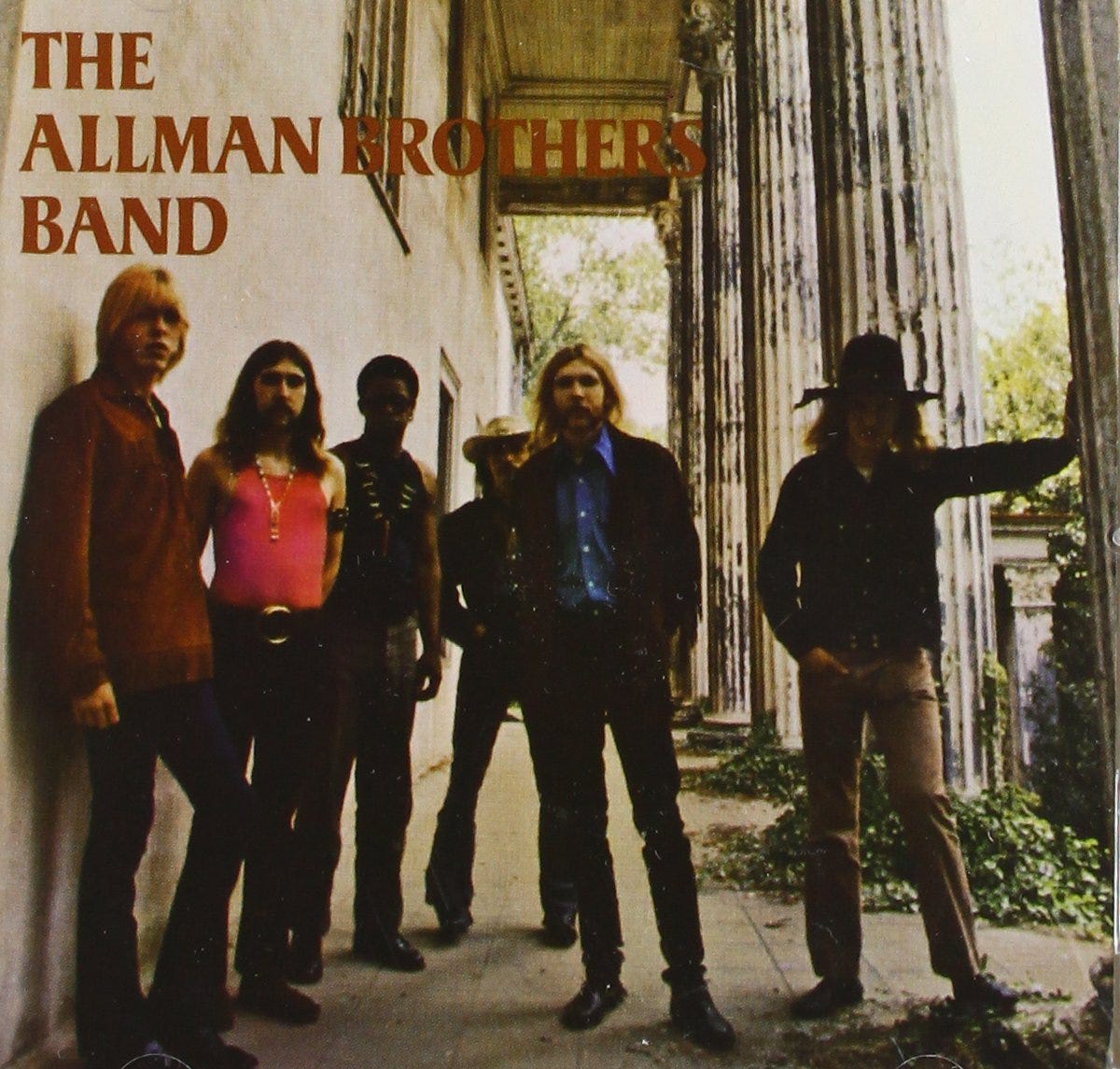

Capricorn was home to the Allman Brothers Band, unquestionably the guiding low-cal of Southern Stone. The Allmans pioneered a winding, bluesy fashion that leant into the book of British stone while maintaining a lithe improvisatory bent. They sounded like nobody else in 1969 only soon at that place would be endless groups that would sound like them, many of them claiming Capricorn Records every bit their own. Capricorn was the hub of Southern Rock but the music had an important outpost a bit farther southward in Jacksonville, Florida, where Lynyrd Skynyrd sounded tougher, angrier and altogether more rebellious.

The Allman Brothers Band and Lynyrd Skynyrd seemed to exist on two carve up ends of the same centrality. With their blend of blues, soul, jazz and rock, the Allman Brothers Ring reflected the emerging New South, where cultures intermingled in means that seemed incommunicable a decade prior. The Allmans were integrated racially, too, which was instrumental in helping forge a refurbished prototype of the Due south. Daniels claimed later "I think the Allman Brothers having a blackness guy in the grouping at that time was a existent heart-opener for a lot of people outside the south."

If the Allmans represented forward move, Skynyrd appeared to represent a backlash to progression. This perception wasn't necessarily authentic, only the subtleties of Ronnie Van Zant's songwriting could exist lost in his ring's triple guitar set on or his lyrics about segregationist George Wallace, not to mention the Amalgamated Flag flying at Skynyrd concerts. The Stars and Confined were an uncommon sight in pop culture in the early '70s but would become familiar a decade later.

Between these two extremes lay Charlie Daniels. A native of Wilmington, Due north Carolina, Charlie Daniels was born on Oct 28, 1936, making him a full decade older than Duane and Gregg Allman, Ronnie Van Zant, Toy Caldwell of the Marshall Tucker Band — any other musician that could exist conceivably called a Southern Rock peer. Charlie was from a different generation, ane who could remember a time before stone & roll, and i who grew up in the thick of institutional racism. Daniels never denied this, recounting to announcer Marking Kemp in 2004 that he "never went to school with a blackness person one day in my life. My mind was conditioned in such a way that I felt they were an inferior race. That was just the way things were. And the matter about it is, when you're raised that way, when y'all're indoctrinated that way, information technology'southward not even a conscious thing to you. It was a cultural matter."

Where the Allmans and Skynyrd grew upward in the wake of rock & ringlet, Daniels graduated high school in 1955, merely as the Ceremonious Rights Movement gained momentum. It as well was the year Neb Haley took "Stone Around the Clock" to number one and the year Chuck Berry released "Maybellene" — in other words, the twelvemonth rock & ringlet started to break, bringing African Americans into the popular Elevation 10 along with information technology. Daniels grew upward listening to Black music — he claimed "the 1 thing the S has ever washed is respect black music. Whether you respected black PEOPLE or non, you respected the music." Even so, Daniels didn't quite run across a mutual ground between Blackness and White. "For me, it was like this: they had their music and we had our music. And everybody knew that black music was the pacesetter."

Despite this, Daniels started his musical career playing bluegrass in 1953 only he couldn't resist the pull of rock & roll. Moving north to Washington DC after high schoolhouse, he formed a philharmonic chosen the Rockets and played as oft as possible. Through these gigs, he became exposed to jazz and blues and the Black musicians who played it. Daniels slowly started to shed his preconceived notions. He'd later say, "One of the hardest things nigh giving up whatever kind of prejudice is being honest with yourself. Information technology'south not easy to say, 'For nineteen years I've been living and believing a certain way and I'm kickoff to wonder if what I believed is correct.' And then you become a niggling farther and start admitting, 'No, I KNOW what I believed is not right. I have no right to experience that way." In one case Daniels brutal for Black music, he started to empathise the Civil Rights struggle and his mind opened.

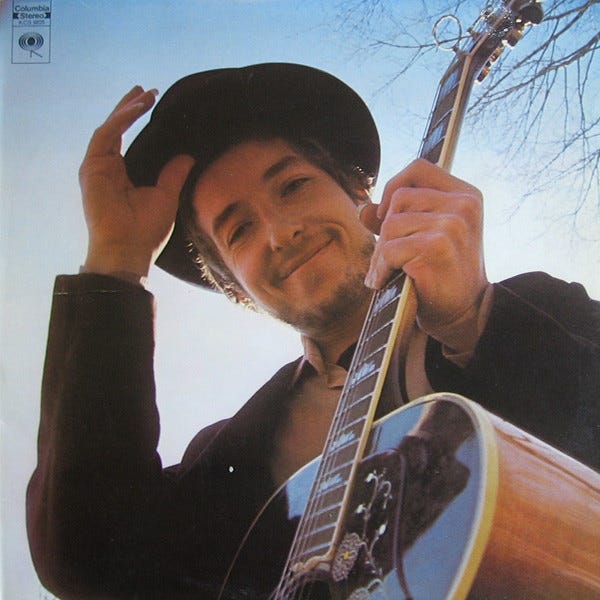

Running alongside this spiritual enkindling came the reality of playing in a working band. Apart from a brief spell in Denver where he toiled away at a stockyard, Daniels played in a bar ring for the better role of twelve years, adapting with the changing fashions. Sometimes, the group built up enough steam to get inside a studio. The first time this happened was in 1959, when they entered a Fort Worth studio with producer Bob Johnston to cut a greasy, bully instrumental called "Jaguar." Johnston convinced the grouping to name themselves later this side and that was the beginning of a long friendship between him and Charlie. Daniels attempted to greenbacks in on the mail-Atomic sci-fi craze with "Robot Romp" in 1960 merely his side by side big break arrived in 1964, when Elvis Presley recorded "It Hurts Me," a song Daniels wrote with Bob Johnston. Information technology went to 29 — a pocket-sized hitting for Elvis, who was in a commercial downturn in '64 — only that wasn't enough to make Daniels abandon the Jaguars only all the same. In 1965, the Jaguars released another 45, a mildly trippy soul single called "The Middle of a Heartache," then slogged through two more than years of constant gigs before Daniels relocated to Nashville on the communication of Johnston. Daniels subsequently explained "I was playing a lot of clubs, and I wanted to get off the road" — a somewhat ironic assessment from a musician who would later accept a reputation as a road warrior — and he settled into the Music City session circuit, receiving an invitation from Johnston to play on Bob Dylan'due south Nashville Skyline in 1969.

Dylan dug Daniels. Charlie was scheduled to play merely one vocal but Bob asked him to sit in for the balance of the session. This interaction is fundamental in Charlie Daniels lore, the moment where Daniels becomes something a chip more than a hotshot session actor — which, by most accounts, he wasn't. He didn't play on many records prior to Nashville Skyline but after Dylan, Daniels became an in-need musician, playing on Ringo Starr's 1970 land record Beaucoups of Blues and produce a Ramblin' Jack Elliott album alongside a pair of Youngbloods platters. Daniels also struck upward a collaboration with the Youngbloods' guitarist Jerry Corbitt. The pair recruited session stars — including Billy Cox, who played bass in Jimi Hendrix's Ring of Gypsies — for a group that lasted no longer than six months. Nevertheless, this is a crucial project for Daniels, pushing him from the studio to the spotlight and sparking his country-rock fusion. Corbitt-Daniels played music that was heavily indebted to the earthy roots fusion of Delaney & Bonnie and Daniels channeled that sound and energy into his eponymous anthology for Capitol in 1971. Before he got to that, he did another Johnston production, playing on Leonard Cohen's 1971 album Songs Of Honey And Hate, along with its accompanying tour.

Daniels had a perceptive read on Cohen's music, i that was born from his years every bit a professional musician. Charlie said Leonard "spoke in poetic means andwas able to communicate with people who had never lived in that world, like myself, and had never been exposed to that side of things. I've never seen everyone that had that softness of touch that could play a gut-cord guitar with the strings tuned downwardly similar that, almost flabby. He has a very unique kind of music, very fragile, that could very easily be bruised or destroyed by somebody being heavy-handed."

"Leonard would stand there with his guitar and sing a vocal and we would try and create something effectually it that would complement it. If in that location was a place that we feel needed enhancing, in one manner or another that'south what we tried to do. The main thing was being part of it merely unobtrusive, very transparent, nada that would distract from his lyric and tune. Y'all could put something in at that place that would mess information technology up real quick."

What's so fascinating about this insight isn't just what it says nearly Cohen's music — it's what it says about how Charlie Daniels perceives music. He'due south non playing from instinct — a dismissal normally lodged at roots musicians — he'due south making considered choices based on how they'd enhance or backbite from a given vocal. Given that he spent and so long playing Tiptop 40 hits for impatient crowds, information technology'southward no surprise Daniels developed a cracking sense of what works musically but he also developed an idea of what an audience wants, and he started to act upon this in 1972, once he signed to the bubblegum label Kama Sutra and developed the first incarnation of the Charlie Daniels Band.

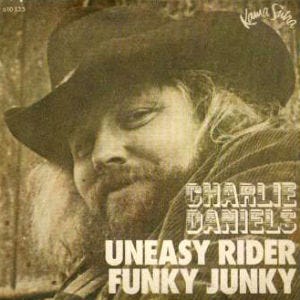

They'd strike gold in 1973, when "Uneasy Rider" became a fluke hit. "Uneasy Rider" rolled along with a finger picked guitar figure, sounding not quite country or folk, but conspicuously belonging to the hippie hangover from the '60s. Of course, the song'south title is a nod to Piece of cake Passenger, the groundbreaking 1969 independent film by Dennis Hopper about ii hippies traveling across the country on their motorcycles, merely Daniels' tale shifts the focus to a long-haired redneck — non exactly a hippie, but somebody who didn't belong with the shit-kickers with crew cuts who represented the southern status quo. These conservatives would be prepare off by some long hair passing through, which is the tale Daniels tells in "Uneasy Rider." Our hero suffers a blown out tire in the middle of Jackson Mississippi, so he tucks his hair underneath his hat and walks into a bar, hoping to pass the time until his Chevrolet is stock-still. Naturally, he's menaced by rednecks anxious to pick a fight with a guy sporting a peace sign on his bumper. Unnerved, he turns the tables on his rivals, claiming that their ringleader is an hole-and-corner lefty.

Daniels later claimed, "The whole indicate of 'Uneasy Rider' was that you don't have to accept crap from people. I was similar, 'Are you gonna allow some guy come and shoot you like they did in that movie?' Hell no, I'm not gonna let some guy shoot me. I'll run over him in my auto if I have to." That's a chip disingenuous considering Charlie'due south narrator in "Uneasy Rider" taunts with provocative, progressive politics. Our narrator tells the gathering mob stories about their chief:

"Would you believe this human being has gone every bit far/as tearing Wallace stickers off the bumpers of cars/And he voted for George McGovern for President/Well, he's a friend of them long haired hippy-blazon pinko fags/I betchya he's even got a commie flag/Tacked upwards on the wall of his garage"

His rival retorts that he'southward a far rightwinger:

"Now simply wait a minute Jim!/you know he'southward lying I been living hither all of my life/I'yard a true-blue follower of Brother John Birch/And I vest to the Antioch Baptist Church building/And I ain't even got a garage, yous tin can call home and inquire my wife"

Now, anybody who wrote those lyrics understands the power of cadence and signifiers, so when our hero winds up escaping the bar and plowing through the bikes of his rivals, he proclaims "I had them all out there steppin and fetchin," information technology's a clear allusion to the comedian whose stage name became a autograph for the stereotype of lazy Black Americans long before Charlie Daniels picked up a guitar.

Then…why did Daniels slide this phrase into his song? Peradventure it's for the aforementioned reason that he transformed Jefferson Davis' Ceremonious-War era Confederate rallying weep "The South Volition Ascension Once again" into "The Due south'southward Gonna Do It," that 1975 hit that celebrated all of the Southern Rockers who emerged in the past 5 years. Charlie after said "The fact is, until and then, neither the Northward nor the Due south knew much about each other….so I call up this music and these bands kind of opened things up in terms of them understanding u.s.a. and usa agreement them," which is somewhat true. Prior to the rise of Southern Rock, there wasn't a widespread understanding of Southernness every bit a unifying factor for musicians, an artful that was a sensibility equally much as a specific sound. Charlie would say, "when people talk virtually southern rock, I say it's not a genre of music — information technology's a genre of people" — and "The South'southward Gonna Practice It," helped codify this because it represented a slight shift in southern rock: it introduced the dabble breakdown, a direct connection to country music that the style otherwise lacked in the previous years.

And by transposing the Jefferson Davis' slogan into an canticle, he emphasized the southern roots of Southern Stone. Like the "steppin and fetchin" line in "Uneasy Passenger," some audiences responded to it equally if it were a dog whistle: the Louisiana co-operative of the Ku Klux Klan put it into radio ads in 1975, a move Charlie quickly denounced. He said, "I'yard damn proud of the South, but I certain as hell am non proud of the Ku Klux Klan. I wrote the song about the land I love and my brothers." Jimmy Carter shared a positive view of "The South's Gonna Do It," adopting the melody as his campaign song for his 1976 Presidential run. In Carter's easily, "The Due south's Gonna Practice Information technology" didn't seem like a retrograde revival of the Confederacy: it was claiming the past for a progressive future, a view Daniels shared at the time. Years after Carter's inauguration, Daniels would still merits "Jimmy Carter is the most honorable human being to hold the part of president of the United states in my lifetime."

By the fourth dimension Carter ascended to the presidency in 1976, the bloom was off the Southern Rock rose. The Allmans were dealing with the aftermath of Duane'south death, Lynyrd Skynyrd would soon lose Ronnie Van Zant and guitarist Steve Gaines in a plane crash in 1977, while other bands simply were getting long in the molar. But Daniels dug into his professional person instincts, deciding his namesake group would be better off if they turned into a working band, churning out a record every year and focusing their attention on concerts, including the yearly Volunteer Jam festival that he launched in 1974.

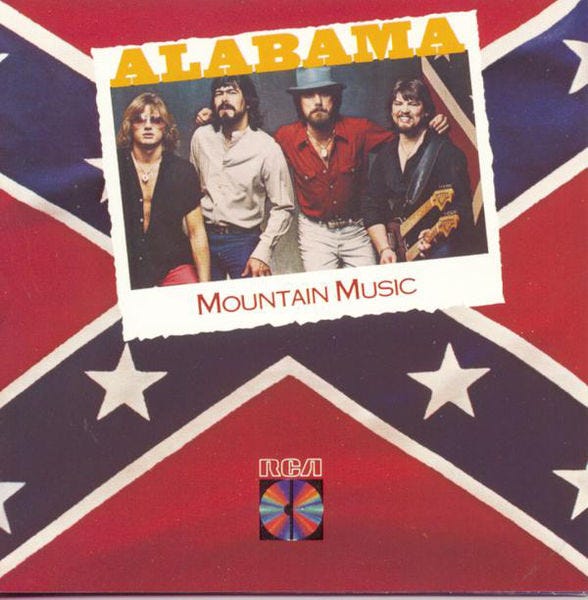

During the late '70s, Outlaw Country — a Nashville variation of Southern rebellion, one focused on songwriters and swagger, not jams — overtook Southern Rock, just past 1980, these two '70s phenomenona began to merge, peculiarly in the realm of mainstream state. The music no longer shunned brawny rock production and signifiers of the South became common, including the Confederate flag'southward Stars And Confined, which popped up in the logo for Alabama — a vocal group that never attempted to stone the boat — and on the roof of the General Lee, the auto the Duke Brothers collection in the hitting TV serial the Dukes Of Hazzard, which debuted in 1979.

That was the same year Charlie Daniels Band finally scored an undeniable hit in the form of "The Devil Went Downward To Georgia. This fiddle-fueled talking blues ready to a disco vanquish captured the imagination of pop audiences as thoroughly every bit country crowds, peaking at 3 on the Hot 100 and reaching number ane on Billboard'southward state charts. Mere chart listings can't quite quantify the impact of "The Devil Went Downwardly To Georgia." It not simply became a pop civilization touchstone, it pushed the Charlie Daniels Ring into the pinnacle of the country charts for the first time. Prior to this, the all-time country placement for CDB was reaching 22 with "Wichita Jail" in 1975. "The Devil Went Down To Georgia" transformed Charlie Daniels from a rock artist into a country i: "Long Haired Country Boy," a don't tread on me anthem of southern defiance, was a country hitting five years afterwards its initial release and if "Still In Saigon" made information technology to 22 on the Hot 100 in 1982, it'd be the terminal time he scored better on the popular charts than land.

And, modern land music as a whole wound upward fundamentally changed past what Charlie Daniels kicked off with "The South'southward Gonna Do It." Past fusing hillbilly dabble with guitar boogie, Daniels gave country a rock & roll boot merely his reclaiming of southern pride paved the path for country acts to raise the rebel flag. Different Charlie, who never capitalized on the Confederacy during the '70s, other artists started to speak the quiet part out loud. Seven years later after "The Due south's Gonna Practise Information technology," Hank Williams Jr cut "The S'south Gonna Rattle Once more," which wasn't a celebration of a resurgent progressive South, fifty-fifty if he dropped allusions to Merle Haggard and George Jones and even Charlie Daniels. Where Charlie slyly nodded at the Amalgamated past, Hank Jr sang "y'all tin bet our brag on that rebel flag" and that set the pace for the rest of defiant conservative politics for the residue of the 80s. Daniels also began to take a strident stance, advocating the lynching of drug dealers in his rabble-rousing 1989 hit "A Simple Human being."

By that point, there was no question that the popular perception of the South was that it was politically bourgeois. Maybe information technology was the failure of Carter's presidency, maybe it was the ascent of Ronald Reagan, maybe information technology was a modify in generations but any trace of progressive politics had been erased from the Southern mainstream. If the mainstream changed shape, so did the paradigm of what constituted a redneck. Every bit Mark Kemp put information technology in his Dixie Lullaby, "X to 15 years earlier, a redneck was a fellow who wore his hair brusque and slicked dorsum, was hostile to long-haired hippies who looked like Van Zant or Charlie Daniels, and was loath to have new kinds of music or new ways of thinking. Now, many of the guys who looked like Van Zant and Charlie Daniels WERE the rednecks."

Ever attuned to trends, Charlie Daniels illustrated this shift by revisiting his old hit "Uneasy Rider" in 1988. In this new version, he wasn't the freak stranded in the boondocks, he and his pal Jim were a pair of skillful erstwhile boys cruising along to Houston in a Chevrolet — notably, they're pulling into a large urban city, non a southern outpost. They pull into a bar, walking into detect "a punk rock ring and some orange haired feller singing near suicide." Jim convinces Charlie to stay simply when a woman who "looked like a girl but talked similar a guy" takes Jim to the dancefloor, things go awry, with "this funny looking feller" coming onto Charlie, putting his hand on our hero'south knee. Charlie threatens the guy, who says "I love it when you get that burn in your eye," so Daniels decks him, starting a barroom brawl where information technology'southward revealed that Jim'due south "beautiful daughter was but a beautiful man/And old Jim simply got ill correct there on the floor."

In the original "Uneasy Rider," Charlie Daniels was in fear for his life considering he looked unlike than the cultural conservatives in the south, only in "Uneasy Rider 88" the tables are turned: he's the one who is revolted by somebody who isn't similar him. Daniels himself hasn't changed much — he was still the long haired country boy, the Charlie Daniels Band even so sounded in 1988 as they did in 1978 — simply the times had changed, with cultural politics falling along clear cut lines dividing the urban center from the country, a divide that happened in function to the proudly rebellious South Charlie created with "The South's Gonna Do Information technology."

Source: https://medium.com/@sterlewine/the-souths-gonna-do-it-again-charlie-daniels-the-confederacy-and-the-rise-of-the-new-south-in-ebbce1059d51

0 Response to "Souths Gonna Do It Again Sticker"

Post a Comment